History, Heat, and Hope

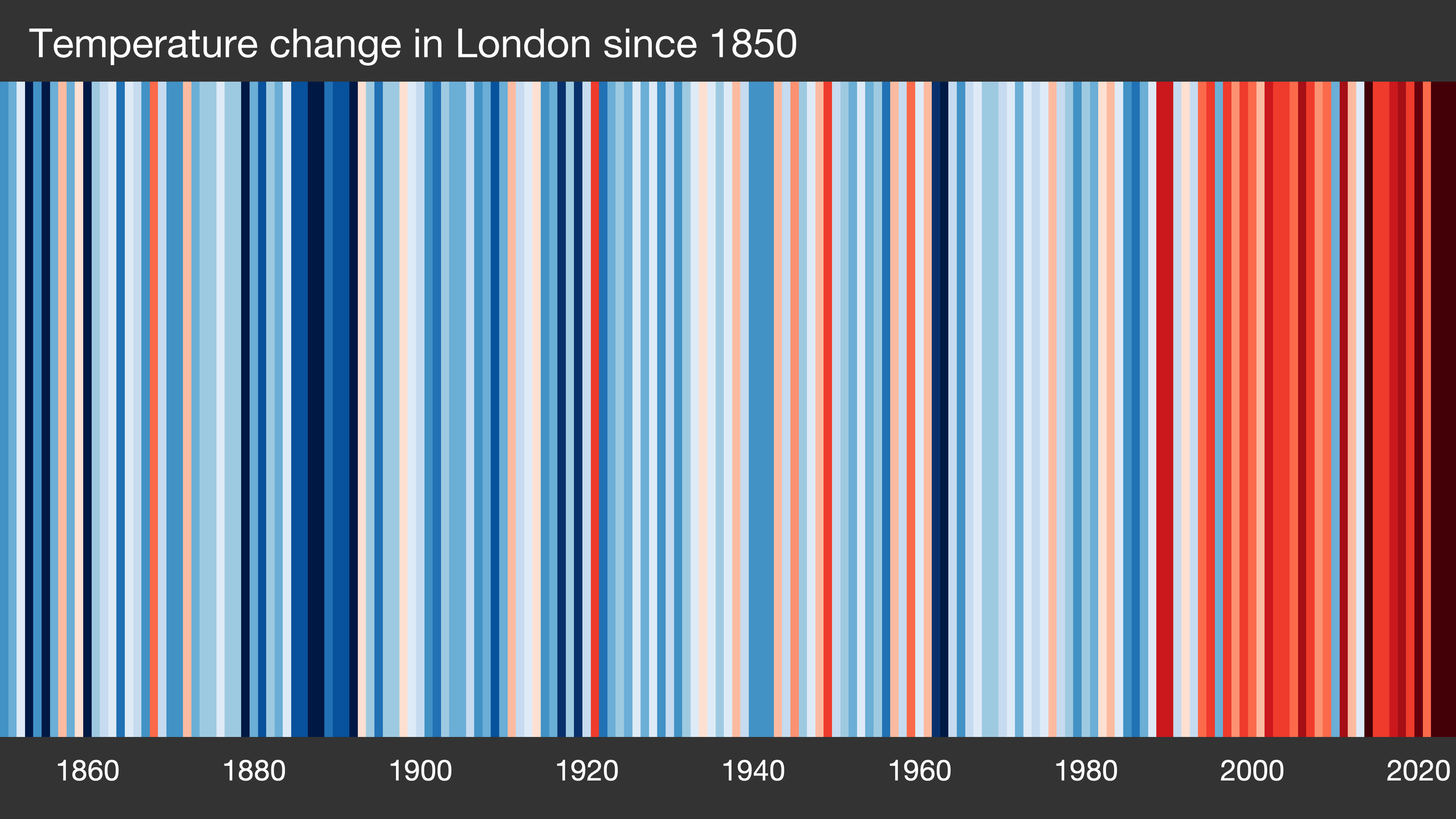

Ed Hawkins, University of Reading, CC BY

According to Met Office climate scientists, the summer of 2025 was the hottest since records began in 1884. The UK’s five warmest summers have all now occurred since the year 2000, pushing the long hot summer of 1976 out of the top five. With the problem of extreme heat so firmly rooted in the present – and hot weather in the past often seeming inconsequential in comparison - it’s not unreasonable to question how history can help us to understand extreme heat and adapt to climate breakdown.

This is a question that’s been in the back of my mind as I’ve conducted oral history interviews and archival research in London, a city often characterised as grey, damp and dreary. But our research is showing that Londoners have lived through extended periods of hot weather in the past. Beyond the matter-of-fact temperature records, we’ve seen how the capital’s residents felt the heat at home and work, often sweating and sweltering in the torrid temperatures of the urban heat island. We’ve also seen how they sought comfort in shady parks and cooling watercourses, on breezy rooftops and beyond the city limits.

But these prolonged periods of hot weather were relatively unusual in the twentieth century, often decades apart. As a result, extreme heat rarely features in the stories that people tell when narrating their lives. Similarly, our collective and official memories seldom engage meaningfully with high temperatures either. When high temperatures do feature in public discourse, the emphasis is often on fun in the sun rather than boiling in the heat.

These historical themes help to explain – but not justify - the present inaction around extreme heat in the UK. Individually and collectively, we have no memorable frame of reference for thinking about or relating to the problems of heat. Through research, creative practice and community engagement, we’re working to reimagine our relationship with summer and highlighting the complex and inequitable experiences of extreme heat in the present.

We’re finding that Londoners continue to show resourcefulness and adaptability, changing their behaviour and habits as the mercury rises. However, we have also seen that many are reaching the limits of their individual resilience in the face of poorly designed housing, disinterested landlords, financial constraints and health conditions. In 2022, around three thousand people died across England because of the high temperatures - but as the Climate Change Committee has noted, there’s still too little action on adapting to heat. Through our work with policymakers and the public, we’re showing how heat is adversely and inequitably affecting the day to day lives of Londoners, bolstering calls for urgent, inclusive and collective action on extreme heat.